Every few years, the Mont Pelerin Society runs an essay competition based on the work of the noted economist and political thinker F. A. Hayek. The essay competition is open to all those under the age of 37.

This year, the contest was on the theme of international institutions and their interaction with liberalism. The prompt is available here.

My entry, which develops an explanation of the trade-offs which face policymakers when integrating two nations’ economies and argues that international economic integration should look more like Australia and New Zealand’s Closer Economic Relations arrangement and less like the European Union, ended up winning first place. You can find a copy of the essay, entitled The Integration Trilemma and Its Implications for International Liberalism, in PDF here. You can also find the full text below.

Title: The Integration Trilemma and Its Implications for International Liberalism

In The Road to Serfdom, Hayek (2001, 242) argues a liberal international order must be neither an ‘omnipotent super-state’ nor a ‘loose association of “free nations”.’ This quote reveals the trade-offs inherent in the construction of international orders – and, indeed, of all state-like institutions – for those who believe in minimising coercion (hereafter liberals): An international order must be sufficiently powerful to prevent coercion of individuals by states but not so powerful as to compound or substitute that coercion with more coercion of individuals of its own. Leviathan must be strong enough to bind others (Hobbes 2008), but weak enough to be bound itself.

In this essay, I develop this timeless trade-off into a trilemma which faces policymakers when establishing international institutions for economic integration. I argue that such arrangements can have only two of: (1) a broad membership; (2) deep integration between the member states; and, (3) the retained ability for states to write their own regulations.

After establishing this framework, I present an argument for how it should inform liberals’ approaches to questions of international economic integration. First, and wherever possible, they should argue for establishing ‘mutual recognition treaties’, which choose to prioritise characteristics (2) and (3) above, with their countries’ closest trading partners. The archetypal example of such an arrangement is the relationship between Australia and New Zealand. Second, as a backstop where such deep relations are impossible, liberals should argue for ad-hoc agreements like free-trade agreements, which prioritise characteristics (1) and (3) above. I argue, contra Hayek (1948) in Interstate Federalism, that liberals should consciously reject proposals for economic unions like the European Union, which prioritise characteristics (1) and (2).

The Trilemma

In modern international economic integration arrangements, the most important provision is not the reduction in direct barriers to trade. Save for recent aberrations mostly driven by the US-China trade war and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, direct trade barriers have fallen precipitously across the world since the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. Apart from special sectors (e.g., automobiles and agriculture), liberals have generally won the battle against blatant protectionism: Tariffs and quotas are usually the first thing to go in any international agreement for integration.

Once direct barriers fall, another important obstacle to international economic integration is regulatory differences between states. Such differences effectively tax firms for operating outside their home jurisdiction, by requiring them to comply with multiple sets of (often incompatible) rules. Moreover, due to the dynamics of regulatory capture, governments often write regulations to favour home firms, increasing these implicit taxes on imports. Thus, increasing the coherence of the regulatory environment faced by firms trading across borders is typically one of the most important aims of modern integration arrangements.

International arrangements for economic integration can be classified by how they approach this problem of regulatory coherence. On one extreme is a model where state-members decide to give up their ability to make economic regulations to an international decision-maker (or, at least, to recognise the decisions made by that decision-maker as superior to those of their own sovereign decision-makers). On the other is a model where state-members continue to make economic regulations independently, but agree to recognise other state-members’ regulations as equal to their own and accept their regulatory competence totally. The former model is exemplified by the European Union, with its supreme EU law and significant European rule-making bureaucracy. The latter is exemplified by the relationship between Australia and New Zealand, where, with limited exceptions, each nation accepts the approval from the other nation’s regulatory agency as evidence enough of a good’s suitability for sale or a professional’s suitability for service.

If one accepts (as one should) the argument from public choice economics that regulators act to some extent in self-interest, it seems unusual that arrangements of the former type (hereafter economic unions) form at all. After all, regulators should surely vigorously oppose attempts to render them unemployed or, at best, impotent by the imposition of superior international decision-makers above them. Given that regulators are often the very same agencies providing ministers with advice on international integration, it would seem that they should (in self-interest) use their power to advise to doom such projects.

There must, therefore, be some significant political advantage to the economic union model for it to have survived (albeit in a limited number of contexts). This advantage is simple: Trust.

In the alternative model above (hereafter mutual recognition treaties), politicians must be willing to accept the judgements of their counterparts in foreign states as suitable substitutes to their own. The political risks of making such a decision are clear: Voters in country X cannot hold ministers in country Y accountable for their regulatory decisions which, for instance, exposed the public in country X to harmful chemicals. Thus, they are likely to hold their own politicians responsible by proxy, despite those politicians having no ability to directly influence these regulations.

Given this risky proposition, the basic question which faces politicians in country X is whether ministers (and regulators) in country Y face compatible incentives while regulating to those that face them in country X. If we, for simplicity, assume that the only interest of politicians is gaining re-election, this proposition can be stated as follows: If voters in country Y are just as likely to punish politicians for bad regulation in a particular sector as those in country X, politicians in country X can likely rest assured that country Y’s regulations will be sufficient (or at least, will attempt to be sufficient).

The easiest way to assess whether politicians in country X and Y face compatible or similar incentives is to compare the similarity of the political, economic, and institutional circumstances they face. Two countries which were effectively identical in these respects would probably have very similar sets of regulations – both now and into the future. However, if, for example, country X was dramatically poorer than country Y, its regulatory landscape might look very different. For instance, the environmental Kuznets Curve (Dasgupta et al. 2002) suggests that country X could be more willing to accept environmental degradation for economic gain than country Y. That might lead to the approval of products (for instance, defoliants) by regulators in country X for sale in the shared economic market that voters in country Y would prefer were not used. Similarly, if country X and Y have different political traditions, politicians in them might face different constraints when writing regulations, which might result in different regulatory results which may be unpalatable to bureaucrats in country Y, which may make the lives of politicians in country Y more difficult.

Given the large degree of political cost which politicians might face from a bad regulation imposed by their counter-party and the already-unfavourable political economy of trade liberalisation3, politicians are likely to err on the side of caution. Thus, they are likely to conclude mutual recognition treaties only with very similar countries. For most countries, the number of countries which are within the tolerance of politicians for similarity is likely to be small.

By contrast, in an economic union, politicians need only trust international decision-makers. These decision-makers could be directly elected by the people in their home country (e.g., Members of the European Parliament), providing an adequate scapegoat for domestic politicians to avoid accountability. Alternatively, they could be appointed by and (sometimes) subject to a veto override from domestic governments (e.g., European Commissioners). This would retain responsibility with the domestic government, but it would also provide them with power commensurate with that responsibility.

Given the economic union model doesn’t require the trust of other countries’ domestic politicians and bureaucrats, it is likely to be amenable to a much broader membership. Whereas mutual recognition treaties can only be concluded between countries which trust each other to regulate with extraterritorial effect in their own country, economic unions can be concluded between any set of countries which are willing to allow their industries to compete with (and, more importantly, their consumers to choose from) each other on a level playing field, with rules determined by a third party over which they have some control. Obviously, the latter precondition – while still a step too far for many protectionist politicians – requires far less trust.

There is a final, third option for economic integration outside of this dichotomy. It is a much weaker option. This is where the politicians’ establish no new rule of regulatory recognition and no new regulatory authority, but simply – by treaty – agree to a set of regulations which will apply to their countries until they agree to vary them (hereafter ad-hoc treaties). The best examples of this type of regulatory freezing-in-amber come from free-trade agreements (FTAs). For instance, the basic commitment to zero tariffs is one. Changes to copyright and patent terms which are often included in modern FTAs count as well.

Deep economic integration is unlikely to come from such an approach. Contrary to the wishes of Hayekian liberals, the modern regulatory state does not “confine itself to establishing rules applying to general types of situations” (Hayek 2001 p .79). Instead, it writes highly prescriptive regulations that must be often updated to account for technological progress and changes in economic conditions. International treaties are ill-suited for writing and maintaining such regulations. They require the involvement of elected politicians who lack expertise to make specific rules and are likely to take a longer-than-acceptable time to conclude. Put simply, the coordination costs are high. In private markets, firms form when the coordination costs of conducting transactions on an ad-hoc basis are higher than the foregone efficiency benefits of market-based coordination relative to command-and-control coordination within firms (Coase 1937). By analogy, international regulatory agencies (or general rules of mutual recognition) could be expected to form when the expected transaction costs of organising regulations in a particular sector across borders via ad-hoc treaty become higher than the political costs of ceding regulatory power to other decision-makers (either foreign governments or international decision-makers). Thus, absent a desirable but unlikely roll-back of the regulatory state, these ad-hoc treaties can only result in the convergence of a limited subset of regulations and a limited reduction in the regulatory barriers to trade before morphing into one of the two aforementioned models.

Nonetheless, the ad-hoc treaty model does have the advantage (to negotiating politicians) of retaining substantial domestic regulatory sovereignty. Firstly, the limitations identified above imply that substantial aspects of the regulatory state must remain outside the scope of the treaty and thus, within the exclusive competence of domestic regulators. Secondly, even for those regulations covered by the treaty, state-parties can always refuse to assent to any amendments, giving them at least the ability to veto proposals from other state-parties.

Relative to the situation created by mutual recognition treaties, ad-hoc treaty-making requires a much lower level of mutual trust. State-parties must only trust each other to comply with their obligations under international law. If they are worried about future changes in policy in other members, they can rest assured that they can simply veto such policy before it is incorporated in the treaty. By contrast, mutual recognition treaties generally explicitly rule that possibility out, unless the state takes the nuclear option of withdrawing from the treaty altogether. Because the levels of trust required are lower, the universe of possible counter-parties is commensurately larger.

This discussion implies that policymakers face a trilemma when creating institutions for economic integration. If they wish to enable deep integration between the economies, they must make a trade-off between the breadth of membership available (maximised under an economic union model) and the level of regulatory sovereignty retained (maximised under a mutual recognition treaty model). Attempting to have all three will result in an untenable political situation, where firms operating with very different regulations created by very different countries will be able to operate on a level playing field with domestically-regulated firms. As much as we might wish such a situation were possible, it will likely not be, especially in the stricter of the two states. The consumers – or, perhaps more likely, the rent-seekers – who demanded the original regulation in the first place will not be willing to see it entirely undermined by what is essentially the extraterritorial application of foreign laws in their country.

The Choices

Now we have established the options which are available to policymakers, it remains to assess those options against our objectives as liberals.

Regulatory Quality

As Hayek accepts in The Economic Conditions of Interstate Federalism (1948), economic unions result in a regulatory monopoly for the international decision-maker. Due to the operation of the internal market, “[c]ertain forms of economic policy will have to be conducted by the federation or by nobody at all” (Hayek 1948, 266). Thus, we must evaluate whether monopoly international regulators will set more liberal economic policies than the individual un-federated states would have in the counterfactual.

Government failures are unavoidable. They can result from a mere mistake, simple bureaucratic incompetence, or industrial capture. If bad decisions are inescapable, it is preferable that fewer members of a given international order are subjected to them. If one assumes the propensity for government failure is as high for domestic governments as it is for international decision-makers, it makes sense to prefer national governments as rule-makers – because their mistakes affect a smaller population.

However, many government failures are not inescapable in a world of mutual recognition and total free trade. Firms and consumers can simply operate in another member-states’ regime, without sacrificing market access. That increases static efficiency: From a given set of options, market participants can choose the set of rules which suits them best. This, naturally, is not possible where there is only a single set of rules (i.e., the international decision-maker’s) to choose.

The natural result of such choice is, of course, increased dynamic efficiency. Competition acts as a discovery mechanism (Hayek 2002) and as a disciplining mechanism. As Hayek argued later in his career in the case of currencies (1990), when governments are forced to compete against each other for business, they are forced to adopt better practices. This inter-jurisdictional competition is not always unambiguously welfare-improving – see, for instance, Australian states competing with each other to maximise discretionary tax breaks given to favoured firms (Banks 2002) – but, where politicians interests intersect at least partially with the general interest, they can do so – for instance, as (Lemke 2016) found when he found inter-jurisdictional competition increased the speed of liberalisation for the laws which governed married women’s property rights in 19th century America.

However, this intuitive argument must be confronted with the possibility that national governments err more than international decision-makers and do so in a correlated way that makes inter-jurisdictional choice and competition less effective4. Here, we engage with Hayek’s argument in Interstate Federalism that economic unions likely result in less protectionism and less planning.

Hayek argues that any given community’s propensity for central planning varies roughly in line with its homogeneity (1948, 264). This proposed relationship arises from two distinct, but related, arguments: Firstly, that more homogenous societies have less conflicting objectives, making such plans easier to write. For instance, in a society only comprised of farmers of a particular commodity, subsidies for that commodity are likely to be relatively easy to sell5. Secondly, that, where trade-offs do exist, they are easier to sell when the payers have some ties – however illusory – to the recipients. As Hayek puts it in the case of industrial subsidies, “the decisive consideration is that their sacrifice benefits compatriots whose position is familiar to them” (1948, 262). Given that international unions are ipso facto less homogenous than nation-states, these arguments lead to the conclusion that economies with international regulators will be less planned than those with national regulators.

The first of these two arguments assumes that, if agreement cannot be reached between the various constituent members of an economic union, the default result is inaction. That is, if France cannot agree with Germany what the correct subsidy for dairy farmers should be, it will default to nothing. Were this true, it would be a strong argument.

Rather, I would argue that the tendency is the inverse: When international organisations cannot agree, they regulate more, rather than less. The bureaucratic imperative to expand size and scope of government acts, despite any disagreements. Bureaucrats from France, Germany, and Italy may disagree, quite virulently, on the correct course of action, but, following the strong argument of (Niskanen 1968), all three likely agree that it involves the expansion of the state. The result, therefore, is likely not that they agree to disagree and simply move on to the next thorny issue: Instead, they likely resolve their dispute by doing all three of their suggested solutions. Not only does that increase the sum-total of regulation, it also likely increases its complexity and the difficulty and deadweight loss involved in adherence.

The second of these arguments assumes that nationalism is the primary consideration which persuades voters to abandon their self-interest and accept central planning (e.g., protectionism). This leads to the conclusion that, while nationalism can justify trade restrictions (or similar policies) within a single-country trade area, it will fail to inspire support for them in a broader union. Hayek asks: “Is it likely that the French peasant will be willing to pay more for his fertilizer to help the British chemical industry?” (1948, 262).

On the margins, it is likely true that nationalism increases the likelihood for bad policies aimed at industrial protection to be accepted. However, the conventional political-economic logic of ‘disperse benefits and concentrated costs’, which often dooms free trade (see Olson 1971), still applies in an international context: Even if consumers do dislike these higher prices and no longer feel they are justified on nationalistic grounds, they simply do not care enough nor do they have enough political power to have the regulations removed, when compared to the significant and organised interest that the protected classes have in maintaining them. In addition, this argument ignores the relatively common case of shared industries: Belgian consumers might be unwilling to protect French dairy farmers from New Zealand competition by paying higher milk prices, but they are quite willing to protect their own dairy industry by paying said prices and therefore, indirectly, to protect the French farmers. Finally, it ignores the very real possibility of horse-trading. German consumers may dislike the protection that French farmers receive, however, French consumers also likely dislike the protection that German automakers receive: The quid-pro-quo is that each accepts higher prices for the goods they import, in exchange for those they export.

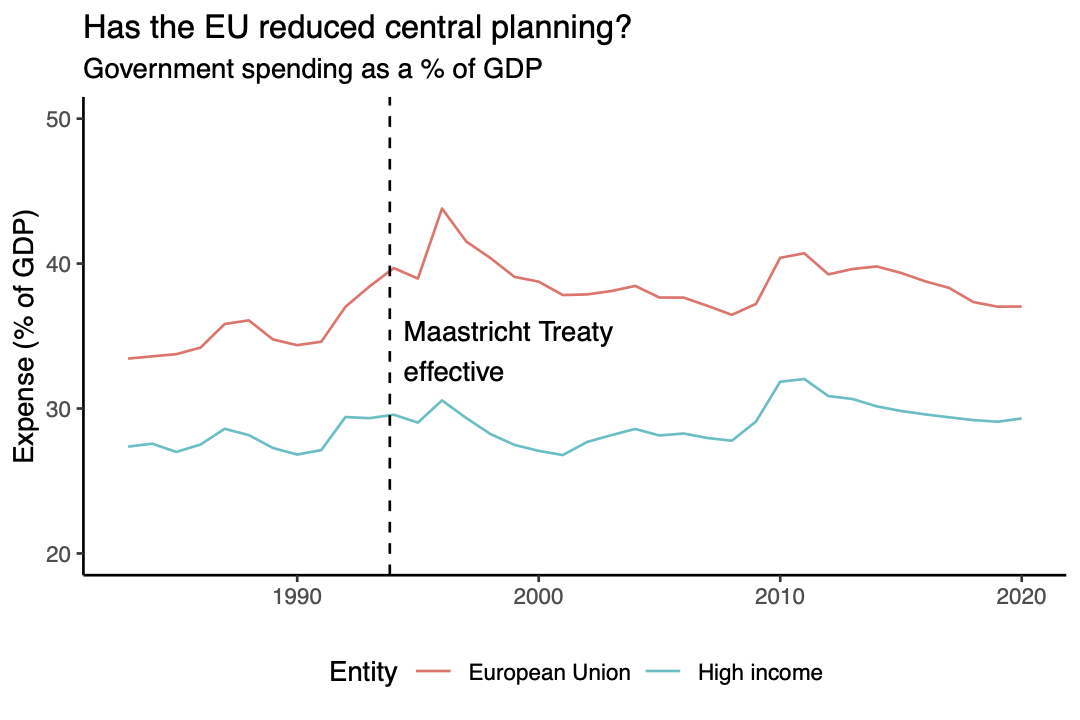

Thus, newer theoretical insights about the behaviour of bureaucracies suggest that, contra (Hayek 1948), economic unions are likely to adopt protectionist and otherwise unwise economic policy. This is reinforced by the European example. Though it is certainly possible that many European states in a non-federated counterfactual would have even more protectionism and planning than they do as EU members, the argument that interstate federation will result in a dramatic reduction in economic planning does not appear to hold water. Using government expenditure as an imperfect proxy for the scale of government intervention in the economy, Figure 1 shows that the gap between EU members and the rich world overall in government spending has not shrunk markedly since the Treaty of Maastricht as this theory might predict. Indeed, over 35% of the EU’s budget goes toward the Common Agricultural Policy (European Parliament 2019) – the world’s largest farm subsidy system and a clear example of protectionist economic planning.

These arguments taken together lead to the conclusion that a mutual recognition treaty will result in preferable regulatory outcomes to an economic union. Moreover, this argument applies even in the case where inter-jurisdictional competition and choice are neutralised by each state making common errors.

The Limits of Integration

In regulatory matters, economic unions and mutual recognition enable roughly the same depth of integration. Firms are allowed to trade in both their home state and a foreign state using the same regulations – the only difference is that in the former case, those regulations are set internationally and in the latter, they are set by the firm’s home government.

However, outside of regulatory matters, economic unions can enable additional integration compared to mutual recognition treaties.

For instance, a common external tariff without an international decision-making body to agree it seems unworkable. The negotiations inherent in making trade deals require international decision-makers which are capable of making trade-offs between sets of intra-union stakeholders in deciding their priorities and what they are willing to concede. The only common trade policies which appear workable are unilateral free trade and a totally static tariff schedule. The former is a laudable goal but a pipe dream in the present political environment. The latter locks out the option of tariff reduction.

Nonetheless, the fact that economic unions can enable deeper integration does not decide the question. We must also consider whether such integrations are wise. Generally, they are not. All of the same problems of reducing inter-jurisdictional choice and competition which make unions inferior to mutual recognition for regulatory purposes apply in these areas too.

Consider trade policy. With independent trade policies but total market access, market forces will encourage governments to liberalise. Firms typically seek to maximise the available market for selling their products. Ceteris paribus, they will prefer, therefore, to produce their goods in the member nation with the most significant market access to external nations. The free trade area created by the mutual recognition treaty means shifting jurisdictions will not cost them access to their former domestic market, increasing the likelihood that they will shift. The natural result of this shift in firms is a shift in workers (possibly enabled by the free movement of people) and a reduction in corporate, income, and consumption tax revenue for the member states with less access, which budget-maximising bureaucrats (see Niskanen 1968) will naturally wish to rectify. The result, therefore, of this newly-satisfiable demand for market access is likely to be that nations will seek to increase the number and value of free trade agreements they have, necessarily reducing their own tariffs to receive access to the foreign market. By contrast, where a single international decision-maker has control over trade policy, this competitive pressure is much lower, because firms cannot access those external markets without exiting the customs union altogether and sacrificing access to their home market.

The Breadth Trade-off

The preceding arguments lead to the conclusion that mutual recognition results in better policy-making than economic union. However, that benefit must be weighed against the naturally constrained scope of mutual recognition treaties to only similar countries.

A narrow membership appears to impose significant costs. For starters, it means that less trade is enabled, simply because there are fewer people included in the overall free trade area. More deeply, if the pre-existing similarity between the member-states is high, their regulations are likely to already be relatively coherent with each other. This means mutual recognition brings fewer static efficiency gains. Moreover, if the incentives on politicians in each country are very similar, they are less likely to reach different conclusions on future issues and thus engender inter-jurisdictional competition with each other. Finally, if the countries are relatively similar, the comparative advantage differences between them are likely to be relatively small, meaning additional trade will be less advantageous than between very different countries.

Nonetheless, there are three arguments which should be considered in mitigation.

Firstly, one of the legacies of European colonial domination in the nineteenth century is that the Earth is characterised by many networks of states which are similar to each other in important respects but are still economically diverse. They often share their colonisers’ language and legal system, for instance. This means that, while the scope of mutual recognition treaties is certainly constrained, there are still non-trivial arrangements which could be made. Take the English-speaking settler colonies6 and the United Kingdom, for instance. These five countries are culturally, legally, and politically similar, so much so that their signals intelligence agencies share almost all of their outputs with each other under the Five Eyes agreement. Thus, they are similar enough that mutual recognition would not be so risky that it would be politically impossible. However, they are also sufficiently distinct from each other economically that freer trade could be very worthwhile. For instance, New Zealand has a comparative advantage in agriculture relative to the other four states, whereas the United Kingdom has a comparative advantage in financial services. One imagines that similar plausible combinations exist among the Hispanophone and Francophone countries of the world.

Secondly, mutual recognition treaties need not be exclusive, unlike economic unions. Consider three countries (X, Y, and Z) where all three are not sufficiently similar to form a multilateral integration arrangement but where Y is similar enough to both X and Z to form such an arrangement with each separately. With bilateral mutual recognition, X would simply be able to accept all goods (or professionals) legal under Y’s laws, without having to accept those which were legal in Y due only to being legal in Z. By contrast, Y could not simultaneously be bound by two economic unions which insist on monopoly control over economic regulations and thus would have to choose which of X and Z it prefers to integrate with. Thus, though mutual recognition treaties may be limited in their breadth when considered individually, their ability to be combined together can partially offset this disadvantage.

Finally, mutual recognition treaties can be combined with basic free-trade agreements to provide some additional breadth. Indeed, such agreements may be easier to conclude under mutual recognition than economic union. As discussed above, nations in mutual recognition arrangements are likely to retain an independent trade policy, unlike those in economic unions. These smaller negotiating units may find it easier to conclude deals than a union negotiating together. This is because they are less likely to contain industries which either threaten or are threatened by their trade partners’ industries. For instance, while Germany has very little industrial overlap with New Zealand’s primarily agricultural and tourism-based economy, small-scale French and Belgian farmers would face intense competition from New Zealand’s highly-efficient dairy industry. Were Germany in control of its own trade policy, it would likely be very willing to conclude a free-trade agreement with New Zealand. However, the existence of Belgian and French resistance makes such a deal much less likely.

Sustainability

Economic integration is only useful for liberals as long as it lasts. Moreover, an integration arrangement should be stable in order to encourage firms to make investments which rely upon it. Thus, in addition to the quality of their regulation and the breadth of their membership and scope, we must measure international arrangements by their sustainability.

As Hayek laments in Interstate Federalism (1948, 262), nationalism is powerful political force. From a merely symbolic standpoint, economic unions are much a more conscious rejection of the nation-state than mere treaties. The trappings of statehood – independent courts, a flag, an anthem, a capital city – come only with a union: As such, even if the union and the treaty imposed the exact same limits on sovereignty, the regular reminders to voters of the abrogation of their national ‘sovereignty’ only come from the union. In any case, the limits on sovereignty are much more circumscribed in a mutual recognition model: Sure, you might have to accept the regulations of the other member-states, but you still retain the ability to regulate your own firms, even if the extent of that power is limited by an exit-option for regulated firms. Given that concerns about national sovereignty are often very important to anti-integration campaigns, a model based on mutual recognition seems more likely to survive such campaigns.

Conclusion

Liberals should support mutual recognition treaties as the first-best way to achieve economic integration. Such treaties achieve what appears impossible by reducing trade barriers while maintaining inter-jurisdictional competition. Though they do come at the expense of broader integration (both in terms of membership and scope), that is mitigated by the availability of alternatives (e.g., free-trade agreements and a series of interlocking bilateral mutual recognition treaties) or the inadvisability of such integration.

By contrast, economic unions like the European Union undermine liberal objectives. They create inescapable monopoly regulators that resolve deadlocks by regulating more, rather than less. Even if they directly allow a reduction in trade barriers between more countries than mutual recognition treaties, they are not the only way to achieve such breadth. Simple free-trade agreements – which are likely easier to conclude outside of an economic union – could suffice, for instance. Thus, liberals should reject economic unions and proposals to give them more power. Instead, they should advocate for a return of power to the nation-state, together with a maintenance of mutual recognition and free trade.

[Word count: 4985]

Policy Analyst, Parliamentary Research Unit, ACT New Zealand↩︎

Incoming BA (History and Economics) Candidate, New College, University of Oxford↩︎

Trade liberalisation is a textbook example of the problem identified by (Olson 1971) that some regulations (e.g., non-tariff regulatory barriers) have disperse costs and concentrated benefits, which (due to various political dynamics) might result in them being retained even if the costs do indeed exceed the benefits.↩︎

That is, if every country is making the same mistake, choosing between them does not offer an effective remedy.↩︎

Naturally, they will also be pointless, because there will be no-one to fund the subsidy except the farmers themselves.↩︎

Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States↩︎